the next big thing is you

(originally published on Medium.com)

tldr:

An optimistic introduction to what could come after the total sovereignty of the VC-funded cycle of disruptions and consolidations

Various new kinds of software, we are endlessly being told, are the Next Big Thing, just about to disrupt like a volcano of New e-Things that will certainly upend all of the things in the next X years. After you’ve read enough in this genre, it turns into a guessing game: will they put X at 5 years, or 9, or 7? You can usually tell by the adjectives in the first three sentences, as the rhetoric is at best overblown Ciceronian pomp and at worst Ted Talk runoff. I like to fill out a bingo card seeing how many rhetorical and ideological crimes I can identify in a given breathless Medium “article” promoting a new startup, written by someone literally overleveraged in the success of its product offering. Here’s a partial list, in case you want to make up bingo cards of your own:

- Misappropriated macroeconomic jargon

- Consequences of disruption and other economic violence naturalized and downplayed via bastardized theories by Darwin or Malthus

- Milton Friedman-esque swipes at central banks as irredeemable cabals that hate freedom

- The word “gamechanger”

- Endruns around anti-trust law dressed up as Quantum Leaps for Mankind

- Any pricepoint under $150/month dismissed as “less than you spend on your coffee every morning”

- A photo of a “founder” or two standing on a stage at a trade show, preferably wearing a cordless mic

- Market prolepsis

- Smarmy appeals to how obviously governments can’t be trusted with the task of regulation, or with “data” itself

Venture capital is the real audience of these missives, and, as Mike Judge’s blunt, Aspie CEO seminally quips on the HBO comedy, Silicon Valley, “The stock is the product.” The winner of this debate tournament is whoever promises the most disruption, since that is what the gamblers came to bet on. As we say in Spanish, “A río revuelto, ganancia de pescadores”—when the waters are choppy, [only] the fisherman comes out ahead. (And no, there are not fisherwomen in this analogy.)

These mammoth disruptions very rarely correspond to giant technical leaps, however; most of them are results of the tiniest of innovations in user experience design, marketing, or convenience engineering. From a computer science point of view, these disruptive apps are apex predators on many levels. They centralize or repackage the data traces left by human experience in a tidy, privatized bureaucracy of monetizable information, but to do so, they stand on the shoulders of data processing giants, mammoth infrastructural investments, decades-long collective refinements funding by private-public partnerships and backroom deals with national-security agencies. In just a few short decades, to the tune of neoliberalism’s mantra (“but who will pay for it, surely not me, or us?”), all of this mammoth infrastructural apparatus was rapidly and irrevocably privatized in both legal substance and public perception. The casino of speculative finance not only wrested away from government any control or even regulatory power over the internet “industry,” but in the process it has also convinced the public that many new, dangerous economic practices and social structures are permanent, natural, and inherent to “the internet age”.

Increasingly, access to monetizable data is distributed even less fairly than access to capital or to credit, while we keep being told ad nauseum that this is just how the internet works, end of story. As public distrust and even anger grows towards the ever-consolidating data traps holding our baby photos and high school acquaintances hostage, we are told that there is no alternative to trading privacy and anonymity for access to a public sphere hosted on private servers and monetized for shareholders. The internet has been defined as a giant machine trading us convenience for our data, which it must necessarily convert into fodder for “machine learning” (aka job-eviscerating automation) and dividends for shareholders (offshored and undertaxed, if taxed at all). We are told that our private thoughts and personal details are the lifeblood of the whole system, that without our data there is no there there, that no business or information technology or convenience is imaginable without it.

I am here to tell you, dear reader, that the next big thing in software is the opposite of all that naturalized and coercive data profiteering. The Next Big Thing is granular and total control over all the data pertaining to your “account” anywhere you open one, with no other data held there, and none of that data shared with anyone else. The next internet will not be a giant pyramid scheme devised to pry your data from you and then sell it to third parties. The Next Big Thing is not privacy or anonymity, although it includes a systematic right to exercise both a lot more easily and often. The Next Big Thing is granular data sovereignty and more sophisticated interactions of the public and private spheres. The Next Big Thing is Self-Sovereign Identity, as it is called among its devoted nerds. You are the Next Big Thing.

To the non-technical, but politically savvy reader, “sovereignty” might seem a hyperbolic term to use for better data controls, but there is a crucial distinction to be made between having the “right” to have your data “forgotten” by request (a right enforced by government regulation and by after-the-fact fines) on the one hand, and on the other, having the power to easily and conveniently delete your own data anywhere it’s stored (a power guaranteed by the design of, and exerted directly through, the data structures themselves). The latter power is sovereignty; the former right is a 19th century form of liberalism held limply in check by shaky, contingent regulation, the kinks in which are still very much being worked out. And supply-side regulation at that, not the most historically effective or popular at time of press.

But speaking of unpopular supply-side regulations, the European Union has recently started enforcing an ambitious set of supply-side data protections, limits, and regulations, a mammoth piece of continental legislature commonly referred to as GDPR (“General Data Protection Regulation”). It was the result of millions of hours of research and multiparty negotiations, a finely-engineered Great Wall of a law, which basically set out to update aging legal concepts around privacy and consumer protections, disincentivizing coercive and secretive business practices rather than banning them outright.

No one in the industry missed this epochal challenge, particularly no one reading quarter call reports. The data industry was, and remains, shook. Every internet business entangled in the ecosystem of data capture and data processing is currently scrambling to shut down a whole continent of its data harvesting operations, rewriting their already-baroque, hundred-page terms of service contracts and privacy policies statements to reflect newly-obligatory protections of the end-user’s rights. Other than a global tidal wave of emails notifying these end-users about updates to those contracts, a less legally-savvy internet dweller could totally miss the importance of this legal paradigm shift. But lawyers and accountants at massive conglomerates like Google have put serious resources behind simultaneously fighting against and planning for this sea-change for years, even if it could seem they’re still playing catchup today. In fact, most of the key players in the data industry will need many more years of retooling to come into full compliance, and in the meantime they have no choice but to budget in massive non-compliance fines levied by the day. Middle-sized data concerns have, so far, been the hardest hit (relative to their operating budgets), but the future of these legal battles is hard to predict, given the amounts of money and jobs at play, much less the politics. At least insofar as the same was said of the Big Banks after the speculation crisis of 2008, perhaps the Big Data concerns are too big to fail, or at least, so big that their failing in the near future would be a hassle to the interests that the EU represents.

But focusing too much on how GDPR affects the big players in today’s data economy is giving far too little credit to the EU’s long-term vision of competition and protectionism. I, an optimist, see the real long game of GDPR to be one of distracting and slowing Big Data, buying some time for the little guys to keep trying radically new things. In my opinion, an understudied positive outcome of GDPR is that it stacks the investment and licensing cards in favor of any business minimizing its reliance on re-appropriated personal data and psychological manipulation. GDPR is a godsend for everyone trying to build slower tech, more ethical tech, tactical tech that Silicon Valley would not only never invest in, but has historically tried to strangle in the crib to protect its deep investments in the most nefarious forms of surveillance capitalism. (Full disclosure: I live in Berlin and I contribute in small ways to various non-profit and commercial projects, in addition to doing paid research and consulting for an SSI-specialized research firm called The Purple Tornado.)

One thing that GDPR seems specifically geared towards encouraging is new kinds of networking and services built on a foundation of Self-Sovereign Identity, which many glibly (and perhaps inaccurately) summarize as “GDPR-compliant by design” at a time when GDPR compliance seems a distant fever-dream to every large internet company operating in Europe. Much like the nerdier, more public-sector-oriented corners of the broader blockchain ecosystem, or the peer-to-peer networking scene, self-sovereign identity is currently more of a community than an industry, with engineers and ideologues heavily represented at conferences without much of the smell of money in the air. There are a few standards organizations working out the interoperability of future large-scale platforms and infrastructure projects, and these have, to date, been relatively good about keeping a place at the table for smaller, non-profit players and government initiatives. There are conferences and whitepapers, there are roundtables at Davos and reports by industry futurists and public-good technologists. There are small, closely-watch trials being run of government systems built on a foundation of SSI in Northern Europe, Switzerland, and Canada.

For obvious reasons, there aren’t huge pots of speculative capital rushing this or that specific initiative to market; for the most part, SSI is starting small and open-source, mostly funded by government grants and long-view R&D investments from industry giants. Of the few companies incorporated and running a payroll already, a surprisingly high portion are B-corps, “social enterprises,” and true, independent non-profits. SSI tech is not coming soon to the walled garden of a cellphone app store near you. But if you follow the weirder, more cutting-edge trade papers and tech conferences, you might hear whispers blowing through the trees.

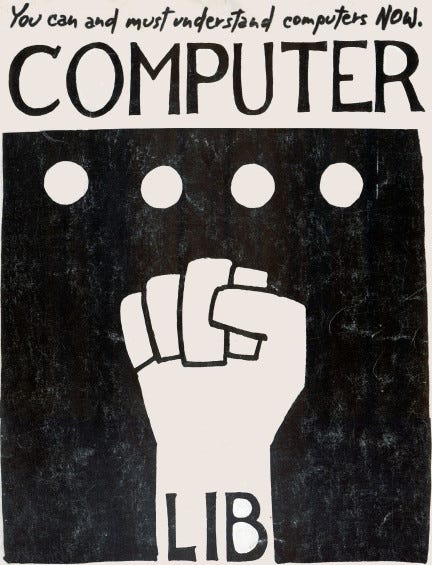

In many ways, SSI is not a bold new vision of the internet, but a return to the foundations of the internet, when the costs of building new infrastructure were still openly shared and the Sharing Economy hadn’t been patented and monetized yet. (To those that would challenge such a linear intellectual history, I would perhaps caveat this reference to the “foundational” vision of the internet as perhaps a tad more indebted to Ted Nelson than to Tim Berners-Lee.) If anything, GDPR crystallized and acted on decades of mounting unease with which the global middle class watched an increasingly homogenous and overtly neoliberal software industry bully all other industries and governments worldwide. GDPR is hardly a perfect law and I would hate to come across as a cheerleader for it, but it has proven a decisive move to shift the ground under the most powerful industry on earth, disincentivizing business models that it implicitly designated as toxic and protecting a space in which to experiment with new ones. At its best, that space will foment scrappy, righteous alternatives (and yes, more startups, for better or worse) that no one will tell you about on pay-to-play information platforms like Facebook or Google News. Or, to put it another way, that no one has borrowed enough venture capital to pay Facebook and Instagram to spread the word about, at their current rates.

Back to brass tacks: what does an internet built on the basis of self-sovereign identity actually look like? How can you retain “sovereign” control over your data if it’s still being stored on a company’s servers and processed to do cool stuff with it?

First off, there is far less of your data going to each company and the companies aren’t sharing it between them, so there is a lot less data at play in any given transaction. Indeed, limiting each transaction or account’s data access to the “minimum data necessary” is a kind of mantra to the most hard-line SSI thinkers. And to be clear, these hard-liners have a pretty solid point about “SSO” (single sign-on), the user-friendly password workaround that give the google/facebook duopoly access to the lion’s share of personal data on earth. Every account you access “through” a facebook or google account gets lumped in with all the data facebook or google already got from you directly, making the “files” that data brokers legally gather on each of us massive archives by comparison to what the East German secret police kept in filing cabinets on its most suspicious and free-thinking citizens.

Why is it so easy for shady data brokerage companies to collate all your data from diverse sources and sell those composites on the open market legally? Why are there copies of your address and social security number on every server and cloud on earth, if all you really need to prove is age here, address there, valid driver’s license or car insurance in a few cases? How did we get to a place in history where it is so terrifyingly easy to track the location of anyone by their mobile phone number? Not by using the minimum data necessary, for starters, and for the profits to outweigh the costs of misusing data, lying to the people that generate it, and selling it to the highest bidder.

Secondly, your “sovereignty” over the valuable and scarce data you do choose to give out hinges on complex systems of cryptography: the shift in power on the social level is effected by a shift in data structures whereby the access you grant others to your data is enforced by the lending, granting, and changing of “keys” and “locks”. (For the highly non-technical, just remember the worst breakup of your life, whether personal or professional, and that moment when you think to yourself: “What if I change the locks while they’re out?”).

In a cryptographically-enforced data sovereignty model, you prove your identity each time you sign in by presenting a one-time cryptographic “key” that the site then uses to encrypt your data anywhere it is stored or transmitted, aka, anywhere it could be hacked or breached. Your data is meaningless without temporary and revocable access to a key that lives in your private wallet. In the case of most current SSI pilots and betas, that key lives in a MetaMask wallet or something similar– a browser add-on or app that securely stores your key to various accounts. Alternative storage methods exist as well, for more complicated security situations. To put it another way, every time you log off, you pull your key out of the lock and all the core, protected data of your account gets instantly encrypted back into gobbledygook; until you log back in, no one, not even the site itself, should be able to read, much less change or sell, any of it.

The “attack surfaces” for malfeasance or unauthorized access to your data are not reduced to zero, but they are smaller, and enforcing fair play on the remaining ones might only be possible if the core code is, if not completely open, at least periodically reviewed by neutral third parties, be they governments, competitors, or white-hats. From the end-user’s point of view, all this translates to a simpler social contract: you have at no point traded or “sold” your data to a company that doesn’t have powerful access to it even while it’s processing it. You have rented your data out to one party, and you can effectively erase it yourself without logging in to that party’s platform, simply by revoking the access credentials you issued to the site.

This might seem like an overzealously individualistic foundation for a new digital economy, but many see it as more akin to double-entry bookkeeping, forcing the designers and builders of data systems to factor user privacy and more thoughtful data design into their core architecture rather than dismissing data breaches and complex user needs as “externalities” or “corner-cases” for the lawyers to worry about later. As anyone who has worked in information security can tell you, the vast majority of data systems were not (and are still not) designed with security or privacy as core functions; instead, they are built insecurely, shown to investors, and then at the last minute, just before rushing them to market, they have flimsy security and privacy controls “bolted on” after the fact.

This organizational dysfunction within the industry might have been less consequential in earlier moment in the history of capitalism, but in this one, there is a worldwide shortage of qualified information security professionals keeping those controls bolted on, and a rapidly growing black market for, shall we say, informal information security professionals trying to loosen those bolts day in and day out. “Web 2.0”, as some people call our current dominant model of social media and other platforms powered by personal data and surveillance, has evolved from a global village to a hacker’s paradise, a data broker’s fire-sale, and a private, cautious person’s hellscape in less than two decades.

Scrapping it all and starting over is starting to sound like a good idea to whole swathes of the world’s population. If we get lucky, Web 3.0 will be a lot less vertically-consolidated, powered by collectively-governed systems and peer-to-peer networks, with a lot less robber-barons and stock-rich oligopolies moving fast and breaking shit. Maybe the coming internet will be a much smaller, quieter, slower, and more humble internet that, plainly put, just does less and disrupts nothing at all. I can almost guarantee it will be drastically less convenient, at least for the first generation or two. But if that’s the price of getting the teeth of the data vampires out of our necks, it might be worth a shot. Maybe we’re drunk on seemingly boundless convenience, and it would do us some good to build something a little more slowly and empathetically for a change.